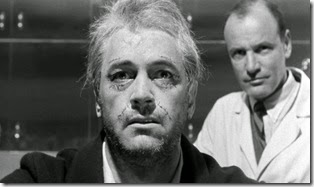

Based on David Ely’s 1963 novel of the same name, Seconds (1966) is a disturbing science fiction—and, I would go as far as to say horror—film about a man who completely takes on a new identity to escape his meaningless suburban lifestyle. Director John Frankenheimer, along with cinematographer James Wong Howe, depicts a stark vision of a world where lives can be created or taken by an underground company headed by a man who looks and sounds a lot like Harry S. Truman (Will Geer). The story itself is so bizarre that it is frightening, and Howe’s voyeuristic cinematography and Jerry Goldsmith’s

On his nightly commute from his New York banking job to his suburban home in Scarsdale, Arthur Hamilton (John Randolph) is given a scrap of paper with an address written on it. Later that evening he receives a phone call from a man claiming to be his dead best friend, Charlie (Murray Hamilton), who attempts to convince him to change his life. What happens next is a series of shockingly matter-of-fact conversations between Arthur and the “Company”. It seems that they can help him extricate himself from his empty existence, in which he no longer shares intimacy with his wife (Frances Reid), sees his married daughter, or enjoys his job. All he has to do is set up a trust worth $30,000 to handle his transition—a cadaver must be procured for his “death”; extensive plastic

![Seconds - 1966.avi_snapshot_00.20.53_[2012.08.08_23.55.17] Seconds - 1966.avi_snapshot_00.20.53_[2012.08.08_23.55.17]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEggLW3BU2Gl5GIbaMsEbGcGY3CII1ovT9N7_yxwmv0VwPDA_LRTZQp_I5pAnXWW0rjmNs-h2b_h19TTyiF5Oey12vk96tje_rLOsaPJnud6S6UBDbZBJS1XwMEDxNEpW8bHTC_GPc84NcE/?imgmax=800)

Of course, such disturbing images deserved to be set to an equally disturbing soundtrack. While it has a sound all its own, Jerry Goldsmith’s soundtrack seems to pay homage to Bach’s Baroque style. Filled with imposing organs, melodic strings, and eerie 60s electronic music, the soundtrack is just as disquieting as the film’s subject matter.

Overall, while I must admit that the story is a bit far-fetched, it is also so disturbing that I couldn’t help but be drawn into it. It also helps that it was expertly filmed and that the soundtrack only enhanced the terror of the narrative.

0 comments:

Post a Comment