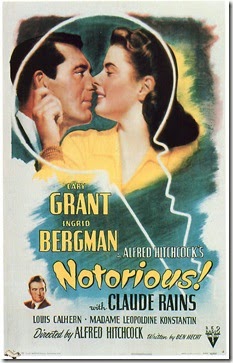

Without a doubt, Notorious (1946) is my all-time favorite Alfred Hitchcock movie. At its core, it’s a romantic spy thriller, but there is so much more to it than Cary Grant and Ingrid Bergman sneaking three second kisses one after the other while engaging in espionage against the Nazis. Yes, it’s filled with suspense and sexual tension, but the film, at least for me, is also a surprisingly sharp analysis of human frailty and morality. As if the story weren’t enough, Notorious also has the best cinematography of any of Hitchcock’s black and white films (and some might argue, his entire oeuvre).

The most important theme in Notorious is the idea of trust, which makes sense because it’s about tradecraft (spying). Still, the way the theme is developed and carried out throughout the story is quite clever. First, Alicia and Devlin’s first meeting is based on deception, as he pretends to b

Alicia: The time has come when you must tell me you have a wife and two adorable children and this madness between us can't go on any longer.

Devlin: Bet you've heard that line often enough.

Alicia: Right below the belt every time. That isn't fair, Dev.

Of course, the worst part is that Alicia is recruited as a spy because of her notorious reputation. The Government has no qualms about prostituting this woman for their po

The first scenario is what I like to refer to as the hangover scene. The scene opens with a close-up of a glass of Alka Seltzer, with Alicia in the background, lying on a bed. The camera then zooms out and switches to what Alicia sees. Hung over and seeing things cockeyed, she sees a man, at a titled angle, standing in the shadow of the doorway. As he comes closer, and she is lying on her back in obvious pain, the camera flips upside down and we see a fuzzy, backlit Devlin. Without a doubt, this is probably the most creatively shot hangover scene ever.

I also find the tea cup scene (yes, they were drinking coffee, but it’s looks like a tea cup), or what I call “Tea is served”, near the end of Notorious to be exceptionally well done. By this point in the story the tea cup has become it’s own Hitchcockian motif, and the audience is aware that Alex and his mother are well on their way to killing Alicia with poison. Again, drink of some sort seems to be Alicia’s undoing. Just as the fizzing Alka Seltzer is the starting focal point in the hangover scene, the tea cup is shot in the forefront of this scene, which opens with one of the Nazis commenting about how poorly Alicia,

I could go on and on about why I’m such a fan of Notorious. Every character was expertly cast, with no one giving a false performance. The story was well paced and quite believable (especially when you consider how many Nazis did end up hiding in Brazil and planning a resurgence of the Reich) and, like almost every Hitchcock picture, meticulously constructed into an edge of your seat thriller, and, in this case, right down to the very last minute on screen. All of these elements, as well as the ones discussed above, are why I am such an admirer of Notorious. Oh, and the MacGuffin is a wine cellar full of wine bottles filled with uranium…thought I’d add that for all the hardcore Hitch fans out there.

0 comments:

Post a Comment