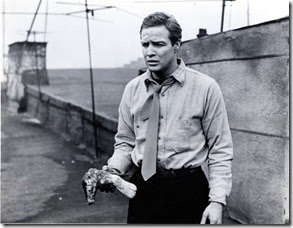

Many modern day viewers of director Elia Kazan’s On the Waterfront (1954) don’t really know what the film is truly about because they are unfamiliar with such things as the Red Scare and method acting. Yet, for students of film history, there is no doubt that On the Waterfront is Kazan’s own personal defense of his naming of names at the HUAC hearings and his belief in the Method acting (although he’d probably not refer to it as such)technique. Perhaps he and screenwriter Budd Schulberg deserved the derision they received for giving the HUAC Committee the names of their friends and colleagues, but that does not negate the fact that they created one of the best dramatic films of their generation. The twelve Academy Award nominations that On the Waterfront received were not a reward for Kazan’s being a “loyal American”—they were earned by mesmerizing actors (Best Actor winner, Marlon Brando; nominated Best Supporting Actors, Lee J. Cobb, Karl Malden, Rod Steiger; and, Best Supporting Actress winner, Eva Marie Saint), a visionary cinematographer (Best Cinematography winner, Boris Kaufman), a gifted editor (Best Editing winner, Gene Milford), a creative art director (Best Art Direction winner, Richard Day), an innovative composer (Best Score nominee, Leonard Bernstein), a daring producer (Best Picture winner, Sam Spiegel), a brilliant screenwriter (Best Screenplay winner, Schulberg), and a revolutionary director (Best Director winner, Kazan). Deride and despise Kazan’s personal actions if you must, but don’t hate the film because it’s an apologetic allegory of Kazan’s actions; instead, embrace it for the striking movie that it is.

So, obviously Terry’s dilemma is a stand-in for Kazan’s decision to

Clearly, Brando is the star of the film. No actor played inner turmoil better, and no character had as much as Terry Malloy. Still, Malden’s turn as Father Barry is probably my favorite performance in the film. The Jesus on Calvary speech he gives in the hull of the ship after Dugan (Pat Henning) is killed is filled with such indignant rage that it raises the hair on my arms each time I see it. I also really enjoy the few scenes that we get to see Steiger in—at this point in his career he was still a nuanced actor and not a complete ham, as evidenced by his turn in The Specialist (1994).

My least favorite performances come from Saint and Cobb. For me, Saint’s Edie is jus

As mentioned above, I thoroughly enjoyed the Christ on Calvary speech and it

And, then there are the scenes which bear the hallmarks of a Kazan picture. The wandering camera along the shoreline as Terry talks with Father Barry, a conversation which we are not privy to, and the confession scene between Terry and Edie probably bear the Kazan signature the most. Throughout the story guilt has been building up inside of Terry to the point that he’s ready to explode, and so when he does come clean to Edie all the audience hears is a squealing steam whistle. For me, although some may disagree, this squealing

So, let’s get to the elephant in the room: why did I only give On the Waterfront three out of four stars? Reason number one, I don’t like how Eva Marie Saint plays Edie. Reason number two, and 95% of why I always leave the film with a bad taste in my mouth, is the ending. There is a complete disconnect in the last ten

0 comments:

Post a Comment