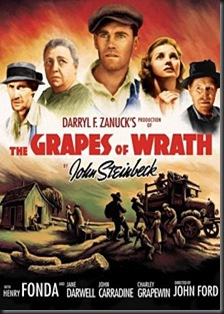

You don’t get more of a Depression-era film than director John Ford’s The Grapes of Wrath (1940). Based on John Steinbeck’s Pulitzer Prize winning novel of the same name, the story follows the displaced Joad family from the Dust Bowl of Oklahoma to the sunny orchards of California. Darryl Zanuck took a chance when he bought the film rights for 20th Century Fox, but in the end it paid off with seven Oscar nominations—two of which earned Oscars for Best Director John Ford and Best Supporting Actress Jane Darwell. While it isn’t surprising that the film was nominated for Best Picture; it is a tad shocking that renowned cinematographer Gregg Toland’s striking images were overlooked by the Academy. You see, the story is gripping and the acting is mesmerizing, but the visuals are what make this film a treasure.

When I read Steinbeck’s 600+ page novel in college I found myself admiring preacher Casy (John Carradine) and rooting for poor Rose-of-Sharon (Dorris Bowden). I also didn’t really like Tom Joad (Henry Fonda) and I could have done without the intercalary chapters. Thankfully, the intercalary sections were left out of the film and what remains is a story that rips your heart out, chops it up, and then feeds it to the pigs. Here you have a poor Oklahoma family thrown off the land their family has worked for generations by both mechanization and the banks. No one seems to care that they have nothing but an old rickety truck loaded to the brim with a few pieces of furniture and articles of clothing. They search out a new life in California, only to find that they are not needed or wanted. Along the way they meet mostly scorn and mistreatment (mostly by land owners and law enforcement), but they do meet a few compassionate people. The most memorable being the diner waitress who sells two peppermint sticks to the children for a penny, when they really cost a dime.

When I read Steinbeck’s 600+ page novel in college I found myself admiring preacher Casy (John Carradine) and rooting for poor Rose-of-Sharon (Dorris Bowden). I also didn’t really like Tom Joad (Henry Fonda) and I could have done without the intercalary chapters. Thankfully, the intercalary sections were left out of the film and what remains is a story that rips your heart out, chops it up, and then feeds it to the pigs. Here you have a poor Oklahoma family thrown off the land their family has worked for generations by both mechanization and the banks. No one seems to care that they have nothing but an old rickety truck loaded to the brim with a few pieces of furniture and articles of clothing. They search out a new life in California, only to find that they are not needed or wanted. Along the way they meet mostly scorn and mistreatment (mostly by land owners and law enforcement), but they do meet a few compassionate people. The most memorable being the diner waitress who sells two peppermint sticks to the children for a penny, when they really cost a dime. While red-baiting was taking a coffee break in 1940 America

, it was still risky to include Steinbeck’s rather socialistic themes. In one memorable scene Tom asks, “What is these 'Reds' anyway? Every time ya turn around, somebody callin' somebody else a Red. What is these 'Reds' anyway?” Steinbeck, and even Ford to a degree, are making the point that anyone who asks to be treated like a human being and be paid a fair wage is viewed as a “red” agitator.

, it was still risky to include Steinbeck’s rather socialistic themes. In one memorable scene Tom asks, “What is these 'Reds' anyway? Every time ya turn around, somebody callin' somebody else a Red. What is these 'Reds' anyway?” Steinbeck, and even Ford to a degree, are making the point that anyone who asks to be treated like a human being and be paid a fair wage is viewed as a “red” agitator. Henry Fonda does a good job of conveying Tom Joad’s underlying seething rage. Rewarded with a Best Actor nomination by the Academy, Fonda plays the embittered Tom as a man who could (and often does) explode at any moment. You can see the resentment Tom feels in the way Fonda moves, looks, and delivers his lines.

In addition to Fonda’s fine acting, Jane Darwell delivers the performance of her life as Ma Joad. It is the simple and quiet way that she goes about building her character into the backbone of the Joad family that I think most people admire. It would have been easy to play up the stereotypical hysterical hillbilly matriarch that some actresses went for, but Darwell is calm, resigned, and resilient in her role.

In addition to Fonda’s fine acting, Jane Darwell delivers the performance of her life as Ma Joad. It is the simple and quiet way that she goes about building her character into the backbone of the Joad family that I think most people admire. It would have been easy to play up the stereotypical hysterical hillbilly matriarch that some actresses went for, but Darwell is calm, resigned, and resilient in her role. The other standout performance is John Carradine’s (one of Ford’s favorite character actors) as Casy. He adds an almost spiritual element to the film—and not because his character is a fallen

preacher, either. He just seems to have a very reverent screen presence, and he delivers his lines in a prayer-like fashion. Casy was my favorite character in the book, and while he doesn’t get as much screen time as one might like, I think Carradine uses what time he gets to make his Casy one of the most memorable things about the film.

preacher, either. He just seems to have a very reverent screen presence, and he delivers his lines in a prayer-like fashion. Casy was my favorite character in the book, and while he doesn’t get as much screen time as one might like, I think Carradine uses what time he gets to make his Casy one of the most memorable things about the film.While Carradine’s Casy is memorable, it is Gregg Toland’s cinematography that steals the entire production. Employing the purity of black and white film, Toland used wide-angle lenses to capture the parched desolation of the Oklahoma plains and the deserted isolation of the desert. How small is man compared to such images? When dealing with capturing the

human element, Toland used deep focus so savagely that you feel uncomfortable looking at the ragged and malnourished people he sets his sights on. He also uses shadows in a very clever way to literally illustrate when someone has something hanging over their head or breathing down their neck. His images are stark, realistic, and uncomfortable—just what the film and the book were trying to convey about the plight of the Joads and thousands others like them.

human element, Toland used deep focus so savagely that you feel uncomfortable looking at the ragged and malnourished people he sets his sights on. He also uses shadows in a very clever way to literally illustrate when someone has something hanging over their head or breathing down their neck. His images are stark, realistic, and uncomfortable—just what the film and the book were trying to convey about the plight of the Joads and thousands others like them. Now, some might be disappointed that I haven’t discussed the biblical references in the film. It’s there—Casy’s murder is like the crucifixion of Christ and the whole trip is like Exodus—but I find this element severally lacking from that of the book (much was cut), so I don’t find it to be that important. What I think makes The Grapes of Wrath an enduring picture is the stunning photography and the nuanced presentation of one of the best examples of Americana during the Great Depression.

0 comments:

Post a Comment