(This is my contribution to the CMBA’s Comedy Classics Blogathon. Please visit http://clamba.blogspot.com/ for more great comedy classic articles.)

Imagine if you will a world in which a nation finds itself weighed down by hard economic times—a world where a select few have much and the majority of people struggle to make ends meet. In this type of world the masses need something or someone to make things seem less dark and hopeless. In 1935 the world was a dark place for many Americans. The Great Depression saw unemployment and

The Marx Brothers made thirteen films (really fourteen, but Humor Risk [1921] doesn’t count, as it was never released); A Night at the Opera (1935) was their sixth film and their first for MGM. They, like the American people, had suffered some setbacks. Their previous film, Duck Soup (1933), had not fared well at the box office or with the critics; thus, effectively ending their working relationship with Paramount. While the world might have seemed insane to most people, they didn’t

While they no longer carried the keys to the asylum, the Marx Brothers still got Thalberg to allow them to choose their writers, George S. Kaufman and Morrie Ryskind, and to showcase their individual talents. Groucho still got to deliver his quick one-liners. Chico still played the wily ethnic, as well as the piano. And, Harpo was still a silent, childlike figure who could play the harp like an angel and leer at women like a pervert. Yes, Zeppo was gone, but while his good looks would sorely me missed, the brothers no longer needed him to play the straight man as they now had the ultimate straight man—an actual story plot!

There are three things that are profanely outrageous about this film: 1) People are starving to death in America, but Mrs. Claypool (Margaret Dumont) is willing to pay $200,000 to the New York Opera Company if it gets her name into society. 2) The reputation and arrogance of tenor Rodolpho (Walter Wolf King) is more respected than the talent and industriousness of tenor Riccardo (Allan Jones). 3) And, everything else. That’s right, everything else.

While the story is held together by the love story of tenor

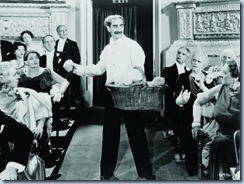

First, you have the famous stateroom scene where Groucho’s character, Otis P. Driftwood, finds himself sardined into a very small room with three stowaways: Riccardo, Tomasso (Harpo), and Fiorello (Chico). The plot says

The second example is the bed-switching skit in Groucho’s hotel. Again, Groucho finds himself playing host to the three stowaways, but now they are illegal immigrants wanted by the police. When Detective Henderson (Robert Emmet O’Connor) comes looking for them and sees three cots in Groucho’s hotel he knows something isn’t right. What ensues is a ridiculous ruse in which Henderson is used as a human carousel to seamlessly transfer an entire bedroom to another room without him knowing. By the end of the ruse the poor detective is thoroughly convinced that he is in an entirely separate room.

The last example, of course, is the final sequence,

I have always thought of the finale as a reflection on America’s upper class citizens in the 1930s—the whole world is obviously on fire, yet they sit passively by and don’t even attempt to throw a glass of water on it! Perhaps I’m a bit subversive in this thinking, but I wouldn’t put it past the Marx Brothers. Maybe this was their small glass of water to an American public thirsting for a bright and hopeful future.

0 comments:

Post a Comment