(Please note that in the 1001 Book, this film is referred to as The Story of the Late Chrysanthemums.)

Sometimes you watch a two-and-a-half hour film and the time flies by, but then there are films like director Kenji Mizoguchi’s The Story of the Last Chrysanthemums (1939), which seem to drag on forever. An obvious

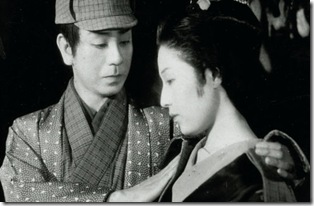

The Story of the Last Chrysanthemums takes place in 1880s Japan and revolves around hammy kabuki actor Kikunosuke (Shotaro Hanayagi). Protected by his famous father’s name, Kikunosuke plods along giving poor performances while everyone in Tokyo ridicules him behind his back. The only person who has enough courage to tell him the truth about his acting is his brother’s wet nurse, Otoku (Kakuko Mori). Every tragedy needs a good setup, and as luck would have it

Self-sacrificing women saturate the world of cinema, but Otoku has to be in the top tier of the all-time greatest ever. While her behavior irritates me beyond measure, Mori’s performance is quite good and makes the movie bearable. Older Asian cinema is permeated with highly stylized acting which can be off-putting to many modern viewers. However, the one good thing

My biggest complaint with The Story of the Last Chrysanthemums is Mizoguchi’s unflinching dedication to the extreme long take. Yes, I know he is attempting to create an atmosphere of introspective reflection, but at some point it just steps over the bounds of acceptability. I think if he had cut most of these scenes in half I would have enjoyed the film much more. Mizoguchi’s contemporary, Ozu, was much more adept at the use of the extreme long take.

Overall, The Story of the Last Chrysanthemums is a study in patience and suffering—both in the movie and watching it. I didn’t hate it, but I most assuredly didn’t love it, either.

0 comments:

Post a Comment