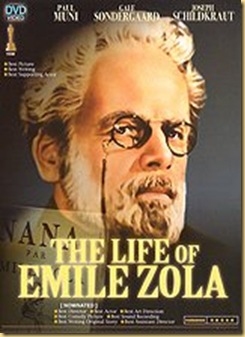

For me, director William Dieterle’s The Life of Emile Zola (1937) is one of those films that I admire but don’t really want to watch over and over again. As a former history teacher it provided a nice tool to visually educate my students about the Dreyfuss Affair, but that’s really it. Yes, it won a Best Picture Oscar, but that had more to do with Heinz Herald, Geza Herczeg, and Norman Reilly Raine’s Oscar-winning screenplay about one of the most scandalous real-life cover-ups to rock France ever, than the overall film production itself.

The best parts of the film (and the bulk of the plot) take place at Zola’s trial for libeling the Army. Mainly, this is due to Donald

Still, what most people remember about the trial is the closing argument Zola delivers to the jury. Muni was known for his biopic portrayals of famous men (James Allen, Louis Pasteur, Benito Juarez and many more), so it is no surprise that

Yet, if it were not for the trial section of this film I don’t think it would merit much consideration. I love Cézanne’s art, but find he gets short-shrift here, which I find disturbing for irrational reasons. I ask you, who is more remembered today: Cézanne or Zola? Ah, but let’s step away from that peeve and mention that we appreciate what Dieterle and his screenwriters did with the Dreyfuss Affair. In a world that was slowly becoming ensnared in anti-Semitism this served as a reminder of how misguided and dangerous it could really be.

0 comments:

Post a Comment