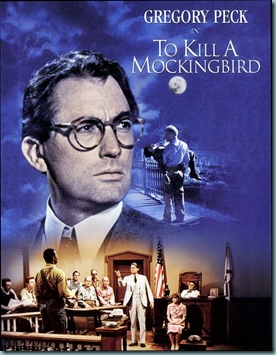

Who doesn’t wish their father was a little bit (or maybe a lot) like Atticus Finch (Gregory Peck)? Kind, soft-spoken, principled, honorable, and patient are the words that spring to

To Kill a Mockingbird (1962) was released at the height of the American Civil Rights Movement. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., had not yet given his famous “I Have a Dream” speech, nor had the nation descended into a fervent anti-war sentiment regarding the Vietnam War. Still, racism and militarism were prevalent themes running wild in the American mindset. In 1962 it was still an acceptable practice in the South (and parts of the North, too) to call African Americans ‘niggers’ and to refer to grown black men as ‘boys’. Miscarriages of justice and vigilante retributions ran rampant through Jim Crow and up to its bitter end with the passage of the various Civil Rights Acts (1957-1968). This is why both the novel and the film To Kill a Mockingbird are such important testaments regarding Southern Americana.

The story is a Southern Gothic tale told from the

I’m sure everyone has their own particular favorite scene from To Kill a Mockingbird—there are so many wonderful ones to pick from—but I expect the most memorable one is when Atticus delivers his closing arguments to an all-white jury. This is probably the scene that

There are many things to like about To Kill a Mockingbird.

Russell Harlan’s black-and-white cinematography is crisp and does an excellent job of setting the Gothic tone. His effort was greatly aided by Alexander Golitzen, Henry Bumstead, and Oliver Emert’s Oscar-winning art direction. Their fictional creation of Maycomb, Alabama harkens back to the

What I think is most telling about To Kill a Mockingbird (both the film and the book) is how it has endured. While I don’t agree that we live in a post-racist society as some may suggest, I do believe that over the last fifty years America has made great strides in this area. When I taught middle school, I always had my eighth graders read the book and then we would watch the movie, and they enjoyed doing both (at least as much as they could). Unlike the hysteria that sometimes surrounds teaching The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, with its constant use of the word ‘nigger’, To Kill a Mockingbird was (at least for me) easily accepted by my students and their families. I suppose having the story told through the eyes of a little girl helped, and the complete condemnation of racism is a plus, too, I’m sure.