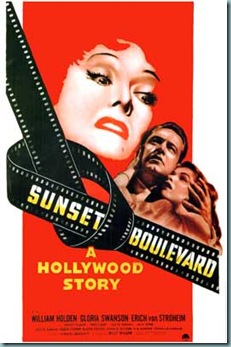

Before there was The Artist (2011) there was director Billy Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard (1950). Both movies shine a very bright light on the plight of a silent film star in the Hollywood Sound Era. Of course, things end much better for George Valentin in The Artist than they do for Norma Desmond (Gloria Swanson) in Sunset Boulevard, but that’s probably why I prefer Norma’s story. It also helps that the acting is insanely good, the script is dark and acidic, and the set design is ostentatiously divine.

Norma’s enormous gilded mansion is a decaying monument to herself—photographs and paintings of her line the walls and furniture tops. The house and Norma are attended by Max (Erich von Stroheim)—a quiet, unassuming former director and husband of Norma. I expect it was rather painful to watch Norma make Joe her gigolo, but Max was the s

I never really liked Gloria Swanson’s silent films and her early forays into the Sound Era were nothing to write home about, either. Yet, there is something mesmerizing about her campy performance as Norma. Of course, Wilder and fellow screenwriters Charles Brackett and D.M. Marshman, Jr., incorporated so much of the real Swanson into Norma that it’s hard to know

The other three principal actors (Holden, Stroheim, and Olson) were also nominated for Academy Awards, but none would have shined quite as bright without Swanson (and in Olson’s case you can only wonder how weak the Best Supporting Actress category was that year?). Holden is convincing as the cynical, world-weary Joe, who finds

In Stroheim’s case, he like Swanson, was playing a caricature of himself. He hadn’t directed a film in nearly 15 years when Wilder asked him to play Max von Mayerling and screen a version of his Queen Kelly (1929) for Norma and Joe to watch (it starred Swanson). When he “directs” the final scene in the movie, you know where Norma comes down the stairs and says, “All right, Mr. DeMille, I'm ready for my close-up,” it must have stung just a bit—Stroheim was considered to be just as good as DeMille in the 1920s but their careers took dramatically different turns in the Sound Era.

But there would have been no standout performances without Wilder’s brilliant script—it drips with acidic venom for the excesses of Hollywood. No element is safe, but the Studio System is his biggest target. When Norma says to Joe the writer, “We didn't need dialogue. We had faces” and “You'll make a rope of words and strangle this business! With a microphone there to catch the last gurgles, and Technicolor to photograph the red, swollen tongues!” Wilder was making a statement about what passed for artistry in (then) modern cinema. Some, like Louis B. Mayer, were outraged by Wilder’s film and he took some heat for it, but in the end he had the last laugh as Sunset Boulevard endures as one of the best films ever about

I would be remiss if I didn’t mention Hans Dreier, John Meehan, Sam Comer, and Moyer for their Oscar-winning art direction and set design. They made good use of the Getty mansion (which was actually located on Wilshire Blvd. before they tore it down and built the beyond boring Harbor Building). Massive in size, every inch was used to display Norma’s ostentatious personality. From the swan-shaped bed to the overcrowded living room, everything screams: Look at me!

Finally, I must commend Franz Waxman’s Oscar-winning film score

0 comments:

Post a Comment