Underappreciated French director Jacques Becker died just a few weeks after filming was completed on Le Trou (The Hole). Becker is primarily known for working as an assistant director to Jean Renoir on such films as Boudu Saved from Drowning (1932), Grand Illusion (1937) and The Rules of the Game (1939), but he was a gifted director in his own right, helming such films as Casque d’or (1952) and Touchez Pas au Grisbi (1954). In a way it is fitting that his last film was about a would-be prison escape, as he himself never fully recovered his health after being imprisoned for a year by the Germans during the Occupation.

Le Trou tells the true story of the 1947 attempted escape of La Santé Prison by

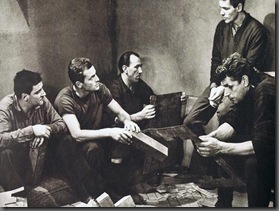

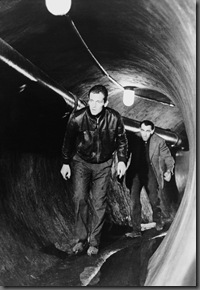

When Gaspard’s (Marc Michel) cellblock undergoes renovations he is reassigned to a cell with four other men. This couldn’t come at a worse time for these men, as they are about to embark on an arduous task: digging a hole out of La Santé Prison.

What makes Le Trou so special is the painstaking effort that Becker and cinematographer Ghislain Cloquet take to capture the various stages of the escape plan. Because most of

For some, the slow (but realistic) manner in which Becker chose to film Le Trou can be off-putting—and some might even say boring. For me, I think it creates an air of suspense and realism which most prison escape movies seem to lack. What stands out most to me, however, is that what I most remember about Le Trou is not the acting, but the time and labor con

0 comments:

Post a Comment