On the morning of November 25, 1970, Yukio Mishima (Ken Ogata) was recognized as Japan’s greatest modern writer. By the end of the day he was viewed as a narcissistic madman, after he and four cadets from his own private army took the general of the 32nd Garrison of the Japanese Armed Forces hostage and then asked that the army join him in bringing the Emperor back to power. When his request was

Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters (1985) depicts this bizarre real-life drama by not only showing the day of rebellion itself but by also focusing on four chapters (and three of the author’s fictional stories) in Mishima’s life: (1) Beauty, (2) Art, (3) Action, and (4) Harmony of Pen and Sword. As each chapter is unfurled the viewer comes to understand Mishima’s almost pathological desire to unite art with the samurai mentality (i.e. harmony of the pen and sword). Supported by the deep pockets of executive producers Francis Ford Coppola and George Lukas, director Paul Schrader helmed a highly stylized film that is told in several tenses: present, flashback and literary, with

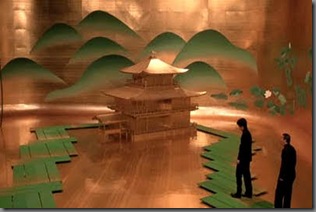

The color composition is what stands out about this movie. When shooting in the present Schrader chose to use a very flat color base, primarily in dreary browns with heavy lighting. This created an atmosphere of unease for the chaos that Mishima was about to release. Flashbacks of what led Mishima to make his fateful decision are shot in reflective black and white, and are always accompanied by voice-over narration from Ogata. It is when the story delves into the literary elements of Mishima’s fictional writings that the movie pops off the screen. Three stories are interwoven into the real-life drama: The Temple of the Golden Pavilion (1956), Kyoko’s House (1959), and Runaway Horses (1969). All are designed as stage plays and end in the suicide/death of the male protagonist.

The second chapter, Kyoko’s House, is effeminate in nature and relies he

While it might not be as colorful as the two previous chapters, Runaway Horses is the most visually striking of the three stories. The lighting is much darker here, and the color tone is primarily in orange, brown and black. In it, a young man decides to lead a revolt against those who support capitalism

The story itself can be difficult to follow if you don’t pay close attention. It’s in Japanese, so while you’re looking at the amazing set designs and hearing Glass’ pounding score in the background, you also have to focus on reading the subtitles. As such, I think this film takes at least two viewings to fully appreciate and understand. The non-linear narrative can be off-putting to some, but I don’t think that it is too disjointed for someone to figure out when and what is happening.

Overall, Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters is an art-house movie that is actually enjoyable to watch. Yes, you have to do a little bit of work, but it does not require much heavy lifting.

0 comments:

Post a Comment