(This article is from guest contributor Sarkoffagus and first appeared at http://classic-film-tv.blogspot.com/. The rating in the title is my own.)

Jack Torrance (Jack Nicholson) takes a job as caretaker of the Overlook Hotel for the winter. A struggling alcoholic who has been sober for five months, he plans to work on his latest “writing project,” while his wife, Wendy (Shelley Duvall), and son, Danny (Danny Lloyd), stay with him in the enormous hotel. Before the

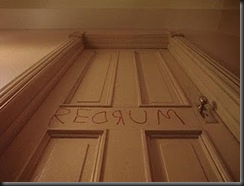

Jack had been informed by the hotel manager of the preceding caretaker, Charles Grady, who murdered his family with an axe before killing himself. Days pass, and Jack sleeps late, repeatedly tosses a ball against the wall, and nods off at the typewriter. As Jack’s behavior becomes progressively more antagonistic towards his wife and son, Danny has visions of mysterious sisters, bloody corridors, and the word “redrum” scrawled on a door. Soon, Jack is seeing people at the hotel, like the bartender, Lloyd, who serves him drinks, and it seems only a matter of time before the agitated writer picks up an axe.

Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining was not generally well received upon its 1980 release in theaters, but like several of Kubrick’s films, The Shining has, over time, garnered more fans and favorable reviews. Kubrick was well known for his rigorous shoots during production, a perfectionist for every shot of his films. His movie prior to The Shining, Barry Lyndon (1975), took an astounding 300 days to complete filming, whereas production for The Shining reportedly lasted over a year. Perhaps because of his lengthy shoots, Kubrick was never genuinely considered an “actor’s director,” as the actors sometimes were simply objects within a highly detailed construct (e.g., the privates standing at attention in 1987’s Full Metal Jacket or Alex and his droogs sitting at the milk bar in 1971’s A Clockwork Orange).

Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining was not generally well received upon its 1980 release in theaters, but like several of Kubrick’s films, The Shining has, over time, garnered more fans and favorable reviews. Kubrick was well known for his rigorous shoots during production, a perfectionist for every shot of his films. His movie prior to The Shining, Barry Lyndon (1975), took an astounding 300 days to complete filming, whereas production for The Shining reportedly lasted over a year. Perhaps because of his lengthy shoots, Kubrick was never genuinely considered an “actor’s director,” as the actors sometimes were simply objects within a highly detailed construct (e.g., the privates standing at attention in 1987’s Full Metal Jacket or Alex and his droogs sitting at the milk bar in 1971’s A Clockwork Orange).

In The Shining, there are seemingly endless shots of far-reaching hallways and characters framed in vast, nearly empty rooms. Something as simple as Wendy bringing Jack his breakfast becomes an arduous task of rolling a service cart for a prolonged distance. Many horror films enclose characters within confined spaces (such as George A. Romero’s 1968 ghoul opus, Night of the Living Dead), but The Shining takes an alternate approach. There is plenty of room to move in the colossal hotel, but, like with so many of the hotel’s elements, it’s pure deceit. The isolated hotel is covered in a severe snow storm, so Danny and his mother can run, and they can even hide, but there truly is no escape.

There have been numerous readings of The Shining, with some critical writings or essays viewing the film as an allegory. While a literal translation of the film’s plot is not likely feasible, it is possible to focus more on its base components. Jack Torrance is either conversing with and being manipulated by ghosts or his mind is disintegrating (not unlike Jack Clayton’s 1961 The Innocents or its source text, Henry James’ The Turn of the Screw). Theories can support either belief, but Kubrick’s infamous concluding shot, closing in on a simple photograph, adds a new element to any potential interpretation.

There have been numerous readings of The Shining, with some critical writings or essays viewing the film as an allegory. While a literal translation of the film’s plot is not likely feasible, it is possible to focus more on its base components. Jack Torrance is either conversing with and being manipulated by ghosts or his mind is disintegrating (not unlike Jack Clayton’s 1961 The Innocents or its source text, Henry James’ The Turn of the Screw). Theories can support either belief, but Kubrick’s infamous concluding shot, closing in on a simple photograph, adds a new element to any potential interpretation.

The Shining was based on the Stephen King novel of the same name, which was adapted by Kubrick and author Diane Johnson. King has been vocal over his dissatisfaction with Kubrick’s film version. The author was most critical of the casting of Nicholson, believing that audiences would immediately see Nicholson as the mentally unstable character, as opposed to watching a man slowly fall apart. In 1997, King adapted his novel and produced a three-part miniseries directed by Mick Garris and starring Steven Weber and Rebecca De Mornay. The television version was filmed in part at the Stanley Hotel in Estes Park, Colorado, the hotel which inspired King’s original novel. Kubrick filmed some of the exteriors for the 1980 film at the Timberline Lodge in Oregon in lieu of the Stanley Hotel, another source of contention for King. (The interiors were filmed at Elstree Studios in England.)

The film’s Steadicam operator, Garrett Brown, invented the Steadicam, which he initially called the “Brown stabilizer.” He first utilized the Steadicam in Bound for Glory (1976) and won great acclaim for Rocky the same year, following Sylvester Stallone up the steps of the Philadelphia Art Museum. His design originally covered the area from the operator’s waist to head, but he was able to employ shots in The Shining at knee height (accomplished by utilizing a wheelchair), as the camera travels behind Danny on a Big Wheel in the Overlook’s hallways. The tracking shots in Kubrick’s film are extraordinary. They are fluid and follow Danny so closely that it gives the impression of being pulled against one’s will, intensifying the dread of the boy turning a corner, as one can never tell what will be standing there.

The film’s Steadicam operator, Garrett Brown, invented the Steadicam, which he initially called the “Brown stabilizer.” He first utilized the Steadicam in Bound for Glory (1976) and won great acclaim for Rocky the same year, following Sylvester Stallone up the steps of the Philadelphia Art Museum. His design originally covered the area from the operator’s waist to head, but he was able to employ shots in The Shining at knee height (accomplished by utilizing a wheelchair), as the camera travels behind Danny on a Big Wheel in the Overlook’s hallways. The tracking shots in Kubrick’s film are extraordinary. They are fluid and follow Danny so closely that it gives the impression of being pulled against one’s will, intensifying the dread of the boy turning a corner, as one can never tell what will be standing there.

Soon after its initial theatrical release, Kubrick pulled the film and cut the ending. The final shot was the same, but there was a preceding scene that did little to explain the events of the movie. If anything, it unnecessarily piled on further intricacies to a labyrinth of ideas. There are apparently production shots, but the filmed scene reportedly no longer exists.

Wendy Carlos and Rachel Elkind composed a score for the film (Carlos had also written the Moog synthesizer music for Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange). However, very little of their music was used, as Kubrick opted for already existing classical music to cover most of the film’s soundtrack. In 2005, Carlos released the original material written for The Shining, with Rediscovering Lost Scores, Vol. 1 and 2 (also featuring selections from A Clockwork Orange and 1982’s Tron).

Though they are often referred to as “twins,” the ghostly Grady sisters in The Shining are simply dressed alike, as the film explains that the two girls are different ages. The well known line -- “Here’s Johnny!” -- was an ad-lib by Nicholson. Clearly a play on Ed McMahon’s introduction of Johnny Carson on The Tonight Show, Stanley Kubrick, who had been living in England for a number of years, reportedly did not comprehend the reference. Carson would later incorporate the scene in an introduction to one of the show’s anniversary specials.

Though they are often referred to as “twins,” the ghostly Grady sisters in The Shining are simply dressed alike, as the film explains that the two girls are different ages. The well known line -- “Here’s Johnny!” -- was an ad-lib by Nicholson. Clearly a play on Ed McMahon’s introduction of Johnny Carson on The Tonight Show, Stanley Kubrick, who had been living in England for a number of years, reportedly did not comprehend the reference. Carson would later incorporate the scene in an introduction to one of the show’s anniversary specials.

The Shining is one of my favorite horror films. I’m a Kubrick fan, and although he didn’t concentrate on the horror genre, the famed director was able to create scenes of sheer intensity and disturbing imagery that sears itself into the viewers’ minds. It’s a movie that, if nothing else, makes me glad that I cannot afford to stay at a gigantic posh hotel.

0 comments:

Post a Comment