In 1933, the Great Depression was steamrolling its way across the globe. Each country dealt with public morale in its own way. To put a little pep in the step of their people the Japanese pushed further into Manchuria and the Germans made Adolf Hitler their leader. In America, we decided to make musicals. Our rationale—poverty is easier to swallow if you’re being entertained by a good song and dance show. And in the end, aren’t dancing shoes more attractive than marching boots?

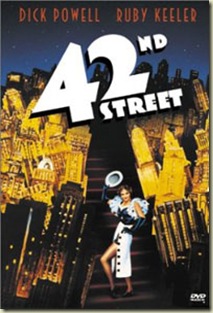

Had it not been for illness, Mervyn LeRoy would have directed this signature backstage musical. He was the one who developed most of the film, but had to hand the directorial reins to Lloyd Bacon after becoming ill—an on the verge of bankruptcy studio just couldn’t wait. Good thing he wasn’t too ill to suggest that then-girlfriend Ginger Rogers play Anytime Annie—her breakthrough role. In addition, this film launched the careers of Dick Powell and Ruby Keeler (Mrs. Al Jolson) and gave little-known choreographer Busby Berkley the opportunity to showcase his amazing talent. When all was said and done, Bacon did a fine job and the film was nominated for a Best Picture Oscar (it lost to Cavalcade).

At the auditions we get a first-hand view of the backstage antics of show business. At the cattle call we meet choreographer Andy Lee (George Stone) and his girlfriend, chorus-girl Lorraine (Una Merkel). We also are introduced to the catty and sassy

Soon after performing the “You’re Getting to Be a Habit with Me” number in a full dress rehearsal (which Bebe Daniels is quite good in), Dorothy sees Peggy getting into a cab with Pat and she becomes jealously enraged. This causes her to drink way too much at her pre-opening party, which leads her to slap and insult Abner. Oh, no you didn’t! Abner now demands that Marsh replace Peggy for her insolence. Really, hours before the opening? Okay, he’ll accept an apology, but first the producers have to get Dorothy away from Pat, whom she has drunkenly called to her hotel. After hearing the producers discussing how to get rid of Pat again, Peggy tries to warn the couple. A drunken Dorothy thinks she’s there to take Pat away from her and attacks her. In this tussle Dorothy takes a tumble and severely injures her ankle. What to do?

This film set the stage for a new type of Hollywood musical and gave birth to the unmistakable Busby Berkeley production number. When people think of 42nd Street they immediately remember the spectacular images he created. In my opinion, Berkeley is the greatest choreographer in film history.

Of course, future Hollywood stars like Dick Powell, Ruby Keeler, and Ginger Rogers got their big break here. Yet, the person I always remember as the standout is Warner Baxter. He was absolutely terrific as the tyrannically-driven director. Personally, I think this was his greatest role—much better than his Oscar winning turn in In Old Arizona. For me, he and the Berkeley production numbers are what makes this such a good film.

0 comments:

Post a Comment