(This is my contribution to the William Wyler Blogathon. Please check out all of the wonderful blogs participating in this great event, which is hosted by The Movie Projector and runs June 24-29.)

Of all the directors screen legend Bette Davis worked with in her storied Hollywood career William Wyler was her favorite. They worked together three times: Jezebel (1938), The Letter (1940), and The Little Foxes (1941)—she received an Academy Award nomination for all three films. No other director knew how to handle

Based on the 1934 Owen Davis play of the same name, Jezebel, which was nominated for five Academy Awards, including Best Picture, tells the tragic story of headstrong New Orleans debutante, Julie Marsden (Davis, in a role that was originated on the stage by her not BFF Miriam Hopkins). When Julie decides to test the love and patience of her longtime on-and-off-again beau Preston Dillard (Henry Fonda) on the cusp of the

The story takes place in 1850s New Orleans, so when the first glance we get of our heroine is her riding a hellish horse and wearing a riding habit we should know she’s a bit progressive for the times in which she lives. The fact that she would wear said riding habit into greet a roomful of “properly” dressed guests to a party she’s late for only compounds the fact that Julie Marsden is obviously a feminist. Still, the riding habit is by far the least memorable of the costumes Davis wears in Jezebel when one remembers the infamous red dress and the virginal white gown she wears to beg Press to take her back. Designed by Orry-Kelly, every costume Davis wears is perfectly matched to the scene in which it is worn. The dress most remember is the red gown that gets poor Julie into all kinds of trouble. To answer Julie’s question upon seeing it: yes, it was saucy! What most people don’t know about the dress is that it was first made out of red satin but when photographed in black and white it looked dull, so the color had to be changed to rust-brown to appear red on film. Still, it is a rather startling dress, especially when it is contrasted against all the white gowns at the Olympus Ball. It fits Davis perfectly and matches Julie’s fiery personality at

That bad behavior, of course, is on full display at the Olympus Ball. After Julie refuses to change her red dress b

Of Davis’ many great performances, Julie Marsden is most probably the most subtle. Davis had Wyler to thank for this, as well as for her Best Actress Oscar statuette. Perhaps one of the reasons most people don’t remember Julie as a bitch is because of the way Wyler asked Davis to play her. Instead of speaking aggressively and dealing death glances with her eyes, Davis was asked to play Julie with a smile on her face and a sweet lilt in her voice. She may have been giving Press hell or inciting duels, but she did it with a sweet Southern smile and a coquettish twinkle in her eye. At first when Wyler asked Davis to play her character like this she didn’t understand and was v

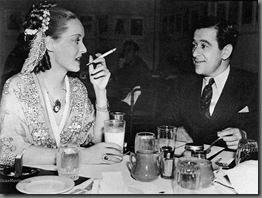

Oddly enough, Jezebel had as much drama happening behind the scenes as it did in front of the camera. For one thing, Wyler and Davis started a torrid affair that reportedly resulted in a pregnancy. And, perhaps to fully encompass the role of Jezebel, who in the words of Aunt Belle (Best Supporting Actress winner Fay Bainter) was “a woman who did evil in the sight of God,” Davis also conducted an affair with Fonda after having a fight with Wyler. It