In 1852 Alexandre Dumas, fils., published his dramatic novel La Dame aux Camelias. After becoming an overwhelming success in France, the novel was adapted into what is considered the most popular stage play ever produced: “Camille”. Based on Dumas’ own relationship with the tuberculosis-ridden courtesan Marie du Plessis, the story has seen countless retellings on both the stage and screen. The most recent film adaptation is Baz Luhrmann’s outstanding musical, Moulin Rouge (2001), starring Nicole Kidman as Satine. And, if you happened to be at the Met on New Year’s Eve you saw the newest (and most energetic) version of Verdi’s “La Traviata”—the operatic retelling of “Camille” (but with a name change to Violetta). Whatever name the female lead is given, the story of “Camille” is one every actress worth her salt wants to play. The New York Times said it best in 1904: “What the North Pole is to the intrepid explorer seeking for fame Camille is to the actress. It is the undiscovered country, always alluring, always fascinating. No other role—unless it be possibly that of Juliet—holds such potent attractiveness for the ambitious woman player.”

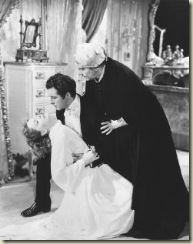

Greta Garbo was an ambitious woman player, and in 1936 she gave her greatest dramatic performance in the film Camille. Aided by the steady hand of director George Cukor,

Garbo delivered the definitive portrayal of the doomed Parisian courtesan. Although she was nominated for a Best Actress Academy Award, Garbo lost to Luise Rainer in The Good Earth. (I have a big issue with this not only because I believe Garbo was more deserving, but because Barbara Stanwyck’s nominated performance in Stella Dallas was better as well.) Sadly, legendary MGM producer Irving Thalberg didn’t live to see this film to its end, but if he had to die and leave one film behind, this was the one.

Garbo delivered the definitive portrayal of the doomed Parisian courtesan. Although she was nominated for a Best Actress Academy Award, Garbo lost to Luise Rainer in The Good Earth. (I have a big issue with this not only because I believe Garbo was more deserving, but because Barbara Stanwyck’s nominated performance in Stella Dallas was better as well.) Sadly, legendary MGM producer Irving Thalberg didn’t live to see this film to its end, but if he had to die and leave one film behind, this was the one. In the film, Garbo plays Marguerite “Camille” Gautier, a beautiful Parisian courtesan plagued with tuberculosis in mid-19th century Paris. Tuberculosis isn’t the only thing Marguerite is plagued with, though—she has a “heart bigger than her purse” and this leads her into a fateful love triangle with the rich Baron de Varville (Henry Daniell) and the handsome, but not rich, Armand Duval (Robert Taylor). While Marguerite obviously loves Arnaud, she constantly pushes him away due to her financial needs, as well as her fear of being in love—she doesn’t believe it lasts. One of the more telling lines about her financial needs comes when Arnaud offers to take her to the country on his seven thousand francs a year and she says she spends more than that in a month. Yet, somehow he convinces her to ditch the Baron and retreat to the country with him.

In the film, Garbo plays Marguerite “Camille” Gautier, a beautiful Parisian courtesan plagued with tuberculosis in mid-19th century Paris. Tuberculosis isn’t the only thing Marguerite is plagued with, though—she has a “heart bigger than her purse” and this leads her into a fateful love triangle with the rich Baron de Varville (Henry Daniell) and the handsome, but not rich, Armand Duval (Robert Taylor). While Marguerite obviously loves Arnaud, she constantly pushes him away due to her financial needs, as well as her fear of being in love—she doesn’t believe it lasts. One of the more telling lines about her financial needs comes when Arnaud offers to take her to the country on his seven thousand francs a year and she says she spends more than that in a month. Yet, somehow he convinces her to ditch the Baron and retreat to the country with him. Once Marguerite makes the difficult decision to leave the Baron, she has to deal with the act of telling him and procuring from him 40,000 francs to cover her debts. Henry Daniell is really good in this scene (actually, he’s good in the entire film, but this is his best scene). He plays it with just the right amount of wounded pride and anger. I especially enjoy watching him tell Marguerite that he’s glad to get rid of such a fool and then slaps her across the face after he gives her the money.

And so for a time, Marguerite and Arnaud live blissfully in the French countryside. Yet, money and Marguerite’s past are still an issue. Their happiness comes to an end

when Arnaud’s father (Lionel Barrymore) pays Marguerite a surprise visit and asks her to give Arnaud up to save his diplomatic career. In every film they appeared in together Barrymore and Garbo always played well off one another, and this scene is probably one of their more memorable. At first, it is a feisty confrontation between the two, but once Monsieur Duval realizes Marguerite loves his son his tone becomes more sympathetic. Still, in the end, he convinces her to give his son up. And this brings us to the three most unforgettable scenes in the film.

when Arnaud’s father (Lionel Barrymore) pays Marguerite a surprise visit and asks her to give Arnaud up to save his diplomatic career. In every film they appeared in together Barrymore and Garbo always played well off one another, and this scene is probably one of their more memorable. At first, it is a feisty confrontation between the two, but once Monsieur Duval realizes Marguerite loves his son his tone becomes more sympathetic. Still, in the end, he convinces her to give his son up. And this brings us to the three most unforgettable scenes in the film. Knowing that she can’t convince Arnaud that she doesn’t love him, she does the only thing she knows will sever their relationship forever: she chooses money and the Baron over him. The look on Robert Taylor’s face when Marguerite walks out the door is priceless. Garbo is more than believably callous in this confrontation.

Hardened by his dismissal from Marguerite, Arnaud seems like a totally different man when he meets Marguerite and the Baron at a casino. Quoting the quintessential line of the play (and a play that they’ve just come from), Arnaud says it is “The story of a man who loved a woman more than his honor and a woman who wanted luxury more than his love.” This leads to a strange face-off between Arnaud and the Baron at the baccarat table, where Arnaud wins a fortune. Still, after all that she’s done to him, Arnaud begs Marguerite to run away with him. When he says that she will be free of him forever if she can say that she loves the Baron, Garbo’s Marguerite makes her final sacrifice and says yes. This is painful to watch, it is so emotionally raw. You compound this with Arnaud’s throwing his winnings at her feet and declaring he owes her nothing now that he has paid his debt, and you have one helluva confrontation. Of course, this leads to a duel in which the Baron is wounded and from which Arnaud must leave the country.

Hardened by his dismissal from Marguerite, Arnaud seems like a totally different man when he meets Marguerite and the Baron at a casino. Quoting the quintessential line of the play (and a play that they’ve just come from), Arnaud says it is “The story of a man who loved a woman more than his honor and a woman who wanted luxury more than his love.” This leads to a strange face-off between Arnaud and the Baron at the baccarat table, where Arnaud wins a fortune. Still, after all that she’s done to him, Arnaud begs Marguerite to run away with him. When he says that she will be free of him forever if she can say that she loves the Baron, Garbo’s Marguerite makes her final sacrifice and says yes. This is painful to watch, it is so emotionally raw. You compound this with Arnaud’s throwing his winnings at her feet and declaring he owes her nothing now that he has paid his debt, and you have one helluva confrontation. Of course, this leads to a duel in which the Baron is wounded and from which Arnaud must leave the country. But what happens in the end, you ask?

It’s a tragic love story, so have some tissues close at hand when you watch to find out that answer. Needless to say, it is a classic ending…one you will never forget.

It’s a tragic love story, so have some tissues close at hand when you watch to find out that answer. Needless to say, it is a classic ending…one you will never forget. This was Garbo’s favorite role. In it she showed just how talented she was. There are few actresses who truly make you believe they are the character they are portraying, but Garbo embodies this role completely. It is truly one of the greatest female screen performances ever.

There are very few films that I rate as excellent, but this is one that I thinks deserves that ranking. The story is a timeless tale of sacrificial love—a favorite theme of mine. The acting is of superior caliber, especially Garbo and Daniell. For those who are enraptured by elegant, luxurious costumes, this film delivers. Garbo looks stunning in all of her gowns (lots of flounces and ruffles) and the men appear dashing and debonair in their 19th century long coats and top hats. Overall, it is a spectacular production that all classic cinema fans should encounter at least once…if not several times.

0 comments:

Post a Comment