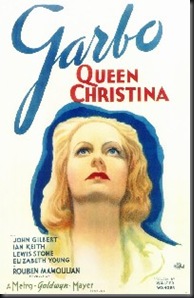

It is difficult to understand how this 1933 racy (this means erotic by 1930s standards) romantic drama ended up being a box-office failure. Here you have one of the most beautiful women in the world, Greta Garbo, playing an amorous 17th century Swedish queen who risks her crown for love. In addition, you have John Gilbert playing her tragic lover—the same John Gilbert she jilted at the altar in 1926. Anyone who read the film magazines back then surely knew Laurence Olivier was supposed to star opposite Garbo, and that it was only after her insistence that Gilbert was given the role. With so much backstory, who could resist this film? Evidently Americans who were too depressed about the Great Depression to watch a tragic romance.

Rouben Mamoulian directed this very loose with the facts historical drama. Screenwriters S.N. Behrman and H.M. Harwood obliviously didn’t read a Swedish history primer, because there are a number of glaring historical inaccuracies (ah, but it was for dramatic effect, so what the heck). The real Christina did not abdicate because of love (or the death of a lover), but

because she wanted to practice Catholicism instead of state sanctioned Lutheranism. However, they did get it right when they hinted at Christina’s lesbian leanings in regards to Ebba (Elizabeth Young), her lady-in-waiting—see the mouth-to-mouth kiss they share in this film (obviously the censor was a man).

Christina ascends to the throne at a very young age after the death of her father, King Gustavus. Her regent, Lord Chancellor Oxenstierna (Lewis Stone), wants to marry her off to her cousin, Prince Charles (Reginald Owen). Prince Charles is a national war

hero and highly revered by the Swedish people. But Christina could care less about Prince Charles and his endless desire to wage war (actually she has a problem with the warmongering). In the palace she has any number of consorts, namely Count Magnus (Ian Keith) and Countess Ebba. Hence, she knows she will not die an old maid, but as she proclaims a “bachelor”. Still, she is a bit hurt when Ebba tells her fiancee that the queen is too domineering. With too much court intrigue and a bit of a bruised ego, Christina finds herself yearning for a change of scenery. And, this brings her to her first meeting with the Spanish envoy, Don Antonio (Gilbert).

Traveling incognito with her trusted bodyguard, Aage (C. Aubrey Smith), she happens upon the Spanish envoy, whose carriage is stuck in the snow. After coming to Don Antonio’s assistance she suggests he spend the night at the nearest inn. This is where things get spicy. Don Antonio mistakenly thinks she’s a boy (she’s dressed like one and has a pageboy haircut), so he thinks nothing of sharing the only available room at the inn with her.

Ah, but why is he strangely attracted to this young man? He soon learns when she undresses in front of a roaring fire. To say he was pleased would be an understatement. They spend the next several days locked in this room enjoying amorous endeavors under fur bedcovers. Where were the censors—in a breadline? Somehow in all of this, she forgets to mention she is the Queen of Sweden.

Instead, the queen thinks they should be properly introduced when he comes to court. Ah, the shocked look Gilbert displays in this scene is priceless. Though he feels slightly used and ridiculed, he eventually forgives her and they consort with one another at court. But there are problems looming: Don Antonio is a Catholic; Count Magnus is jealous; and, the Swedish people want her to marry Prince Charles. The people are so upset that they storm the palace and have to be subdued by the queen herself. Court Magnus is so jealous that he kidnaps Don Antonio and forces Christina to sign a passport for her lover’s return to Spain. This act leads her to abdicate the throne for love and to set her off on a journey to the frontier to meet Don Antonio. Too bad Don Antonio has been mortally wounded in a duel with Magnus—at

least he waits to die in her arms. That’s something, right? She did give up a crown and kingdom for him after all, the least he could do is wait to bleed to death in front of her. Thus, this brings us to the climatic final shot (by cinematographer William Daniels) of Christina on a boat taking her slain lover home to Spain. A glowing, close-up of Garbo’s marvelous face looking out into nothingness. Yeah, I’d say this film could be considered a real downer for Depression-era Americans.

What I like about this film is how wickedly risqué it is. The dialogue is double entendre laced. The love scenes are daring and erotic (for the 1930s), and you have directly hinted at references to homosexuality. It is hard to believe this film was released in 1933. While Camille and Ninotchka are Garbo’s best films, this is her most daring. It is also the film that comes closest to resembling who Garbo was off-screen.

Tuesday, 19 October 2010

Queen Christina (1933) ***

Saturday, 9 October 2010

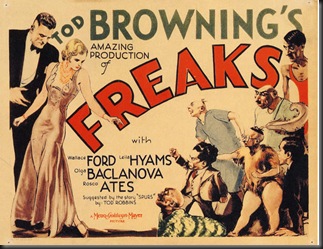

Freaks (1932) **

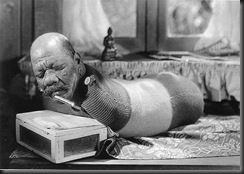

The title of this classic 1932 film is not what one might call politically correct. There are few films in all of cinema that can be classified in the horror realism genre (one might think of The Blair Witch Project or the original Texas Chainsaw Massacre, but they are severely flawed wannabes). Yet, director Tod Browning’s Freaks is one of those few films that blends realism with horror. The freaks in the film’s title are actual 1930s carnival and circus freaks, with all of their deformities on full display. It is said that Browning had the largest casting call of professional freaks ever, and it shows. When watching this film one can’t help but be disturbed by some of the afflictions of these “freaks.” Quite frankly, this is an odd, disturbing film. The film was so shocking that it was actually banned in a number of places. It was later rediscovered on the art house circuit and today is a common staple of TCM’s October schedule.

Browning, of course, is most known for directing Bela Lugosi in the original Dracula (1931). Yet, many film critics consider Freaks to be his masterpiece (not that there was much to choose from) because of his unflinching presentation of another strange reality unfamiliar to the common moviegoer.

The film opens with a carnival barker explaining the events that led to the beautiful “Peacock of the Air”, trapeze artist Cleopatra’s (Olga Baclanova) horrible current state. At this moment, one might prepare oneself for watching a trapeze act gone terribly bad—one would be wrong. Instead, one is treated to one of the

The assembled guests at the wedding table consists of all freaks, sans Cleopatra and Hercules. This is a sight to behold. After consuming way too much alcohol, one of the freaks informs Cleopatra that she is now one of them. Oh, no you didn’t! This, of course, enrages Cleopatra and she launches into full bitch mode by calling her guests “dirty” and “slimy”.

The scene where she informs Hans that she could never love a freak like him and that their marriage is a sham is difficult to watch. The look on Han’s face is just so pitiful. I suppose Harry Earles had a lot of past insults to draw from when it came to playing this scene. Shocked and humiliated, Hans collapses—of course, the poison didn’t help either. Counting their chickens before they’ve hatched (if you’ve seen this film, you know this is a sad attempt at a pun),

While this is not the greatest film you will ever see, it is an interesting watch. The pure shock value of some of the scenes is enough to warrant spending a mere 64 minutes watching Tod Browning’s best film.